|

From Khajuraho, Alyse and I catch a bus and then an overnight train to Varanasi. The train arrives in Varanasi in the stillness before sunrise. We catch a rickshaw down to river's edge, the eternal flow of the Ganges River. In the dark, I sit on a ghat ... and breathe ... and sense the energy of the Ganges ... A young girl walks up with a basket of small hand-woven leaf bowls. Each bowl contains a candle in a bed of pink flower petals, an offering to the Ganges. I buy one, walk down to the Ganges, light the candle and set it out on the water.

It

bobs away in the current and the candle soon burns out,

Dawn breaks ...

There are plenty of men in rowboats along the riverside offering boat rides down the Ganges. We decide to take one.

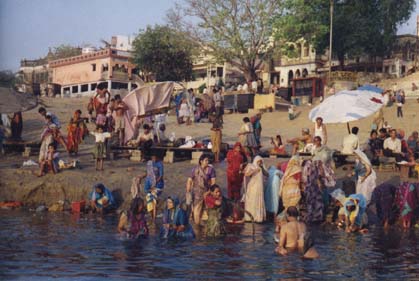

Many Hindus are praying and bathing in the Ganges, men stripped down to loincloths and women in saris. Their prayers become more fervent as the sun begins to rise.

Hindus try to make a pilgrimage to the Ganges at least once in their life to bathe in its waters, which they believe cleanses their soul of sin. Countless tourists in countless rowboats, myself among them, bob in the river's current not 50 feet from one of the most intimate rituals of Hindu society. Varanasi, a city with palpable intensity, lays bare the intimate rituals of an ancient culture. It has been a center of learning for more than two thousand years. It is also a place where people come to die. The Hindu faithful believe they will achieve a break from the reincarnational cycle of birth, death and rebirth if they are cremated on a wood fire here when they die, their ashes scattered in the Ganges. Lepers line some of the streets leading to river's edge, asking for a handout and preparing for death. The smell and feel of death hang heavy in the air. Piles of chopped wood line the paths leading to Harishchandra Ghat, one of Varanasi's two burning ghats. The wood is expensive; those who cannot afford it are cremated in an electric crematorium, which many feel is not as good for one's karma as a wood fire. The very rich are burned on sandalwood, which burns with a nicer smell than ordinary wood. The business of dying. All ashes to ashes, released to Mother Ganga. It's not permitted to take photos of the following, which is why there are no photos here. A human form wrapped in red cloth lies on a pile of large logs at Harishchandra Ghat. The fire is lit. Four foreigners and some twenty Indians sit quietly nearby, contemplating the flames. The red silks and purple cloths that wrap the body crackle, skin burns away and the skeletal form emerges. The fires burns hot, day and night. The air around the two burning ghats is often thick with smoke. Hindu music, celebrational in tone, blasts incessantly from a nearby yellow cement structure. An intimate ritual of Hindu life, the rite of passage from this life, is performed in a very public space. The accessibility of these intimate rituals give Varanasi a riveting intensity.

|